CULTURE | ENVIRONMENT

Art as Activism: Ecofeminism and the Climate Crisis

WORDS BY SHELLEY BUDGEON | 12 FEBRUARY 2024

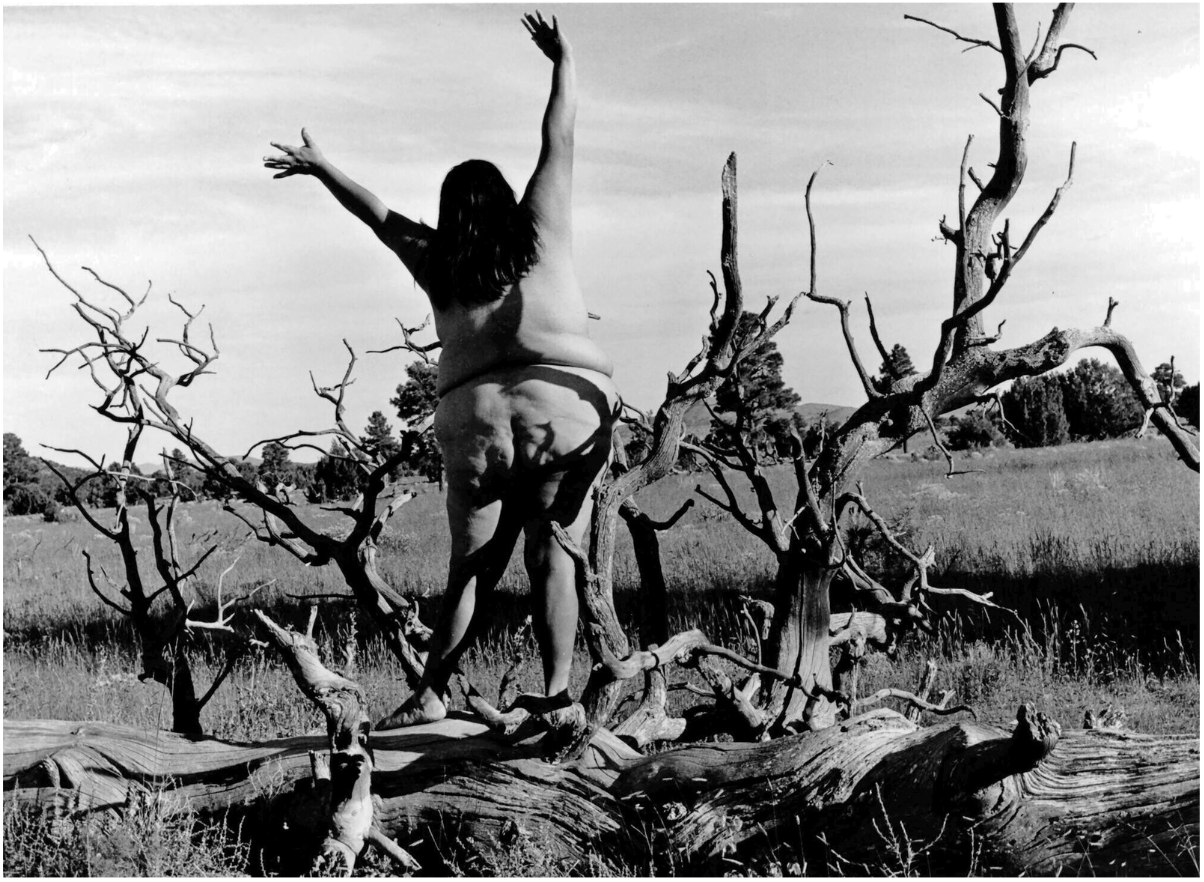

Source: Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016

The art exhibition, Re/Sisters: A Lens on Gender and Ecology recently held at London’s Barbican Centre, featured works

from 50 international women and gender non-conforming artists. Through a series of arresting images and provocative installations,

this exhibition invited the audience to critically reflect upon the logic of domination that drives both gender oppression and the ongoing degradation of the environment.

In 1952, Simone de Beauvoir argued that within patriarchal systems both women and nature are assigned the status of men’s lesser and opposite ‘other’. With this insight, the conceptual foundation was laid for critiques developed by feminists who argued that ‘othering’ made both women and nature subject to patriarchal domination. Decades later, in 1974, Françoise d’Eaubonne identified an intrinsic link between women’s liberation and ecological revolution and coined the term “l’eco-féminisme” to describe this insight. A rich and varied feminist analysis of the deep interconnections between women’s subjugation and the exploitation of nature has since developed.

The art exhibition, Re/Sisters: A Lens on Gender and Ecology recently held at London’s Barbican Centre, draws on this heritage, featuring works by 50 international women and gender non-conforming artists. Through a series of arresting images and provocative installations this exhibition encourages the audience to critically reflect upon the logic of domination that drives gender oppression and ongoing environmental damage. By linking together the intertwined axes of sexism, racism, colonialism, and capitalism with the degradation of nature and the environment, these art works communicated key principles of ecological feminism while also evoking ecologies based on non-hierarchical, multiple interdependencies as an alternative to those which promote exploitation and extraction.

Upon entering the gallery the viewer is confronted with a wall of aerial photographs depicting a range of different sites where economies that exploit nature have left their irreversible mark on the earth. The images in the series, Eyes and Storms, by Simryn Gill resemble lacerations and injuries caused by invasive industrial practices such as open-pit mining and introduce the audience to the first theme in the exhibition, Extractive Economies/Exploding Ecologies. From Australia, to Columbia, to Namibia, the works in these opening galleries demonstrate the effects of ‘exploiting, removal, or exhaustion of natural resources on a massive scale’ and the disproportionate negative impact Indigenous communities, and women, experience as a consequence of the colonial-capitalist mindset that drives overexploitation and turns natural resources into a source of wealth at the expense of the majority – a set of relations devoid of the value of reciprocity.

The second theme explored in the show, Mutation: Protest and Survive, focuses on how the survival of women is intricately entwined with the struggle to preserve nature and life on earth as both are vulnerable to patriarchal violence. These works remind the audience of the history of protest against ecological destruction enacted by women across the globe as they have mobilized against forces of extractivism in the defence of their environments and communities. ‘Mutation’ references the work of the ecofeminist Françoise D’Eaubonne, who used this concept to envision a reversal of man-centred power – not as a transfer of power from men to women – but rather as a liberation of both women and nature through the destruction of power.

Within patriarchal divisions of labour, women are assigned the work required to ensure social reproduction and, as a result, are often the ones who first become aware of alterations to the local environment. The additional work required to mitigate the detrimental impact of those changes also falls to women. In the works exhibited in the theme Earth Maintenance, undervalued care practices associated with women’s social reproductive labour are examined, where care of the ecology is the focus of women’s work. The works demonstrate an ethic care counterposed to the core logic of colonialist capitalism constituted by a masculinist ideology. Imagery in this section portrays caring for the earth as a political practice centred on the demand for ecological justice and accountability for institutions of power.

Images in Performing Ground illustrate the dissolution of the distinction between the human and the more-than-human. Audiences are invited to imagine the merging of human and natural worlds in order to recognise the intercedence of these realms.

The forging of a mutual relationship between these entities symbolizes the undoing of settler-colonial subjugation and hierarchical relationships which have historically led to the domination of indigenous communities and the natural world. Ecofeminist Vandava Shiva, for example, criticises dominant forms of contemporary development and globalization for perpetuating colonial relations, and refers to these practices as ‘maldevelopment’ because, like colonial logic, they presuppose the reduction of both women and nature to passive objects to be acted upon by economic and technological forces.

Capitalist power relations which materialise in land ownership are examined in the galleries named Reclaiming the Commons. Questions about who has the freedom to move through, claim and inhabit space that is increasingly enclosed via acts of private appropriation are invoked. By drawing on the notion of ‘the commons’ these works challenge privatisation and reinstate a notion of egalitarian stewardship in which all members of a community have access to land as a key resource that provides the means for sustenance and female empowerment, particularly as the use of space and place is gendered.

In the final gallery, Liquid Bodies, relationships between human cultures of gender and sexuality, and the world of water are explored. In place of a traditional dualistic structuring of relations, these works celebrate the destabilisation of binaries and envision what might happen if we employed Queer theory to transcend our thinking of the ‘natural’ versus the ‘unnatural’, the ‘alive’ versus ‘not alive’ or the ‘human’ versus the ‘non-human’. Replacing dualism with fluidity confronts Western taxonomic conventions that create polar opposites, wherein certain qualities are denied one group to the benefit of the dominant group. Plumwood argues that rejecting dualisms is key to discrediting mastery of the ‘other’, to thinking inclusively of all beings, and to respecting the agency of the other, whether human or not.

In a time of heightened awareness of the climate crisis, this exhibition contributes to climate activism by communicating the deep and profound role feminism has played in analysing environmental issues. The art works also provide a timely reminder that climate change is not gender neutral – it acts as a threat multiplier that intensifies existing historical and structural inequalities which are unevenly distributed globally. Remedial action must include those most at risk and historically ecofeminists have called for greater inclusion of women within governance structures responsible for environmental policy. The World Women's Congress for a Healthy Planet in 1991 is often hailed as a key point of entry for the inclusion of feminists into UN global environmental conferences concerned with realising sustainable development goals. Those early efforts resulted in formal recognition by various institutions, such as the UNFCCC, who endorse the importance of involving women and men equally in UNFCCC processes and call for the “development and implementation of national climate policies that are gender-responsive by establishing a dedicated agenda item under the Convention addressing issues of gender and climate change and by including overarching text in the Paris Agreement.” Notably, the Re/Sisters exhibition coincided with the COP 28 UN Climate Change Conference which took place in Dubai from 30 November to 13 December 2023. The conference included a series of sessions focused on gender, and numerous advocacy groups, such as SheChangesClimate, continue to increase awareness of the crucial role women will play in accelerating climate action.

While women have advocated for and won inclusion into the formal machinery of climate policy-making and institutions where global decisions are brokered, grassroots activism remains central to feminist ecopolitics. In Switzerland, the KlimaSeniorinnen, a group of women hikers in their 70s, are suing the Swiss government in the European Court of Human Rights for violating their human rights by failing to implement policies that address climate change. Their argument is twofold. Firstly, increasing heat waves and higher temperatures are the result of fossil fuel production and consumption, and secondly, women, particularly those who are older, are more vulnerable to the fatal impact of high temperatures. The end result may fall short of victory, but the process could potentially “enshrine milestones that nudge governments into more stringent climate policy through human rights guarantees.” All of these women were born at time when women did not yet have the right to vote in Switzerland, making this a fitting example of ecofeminism in action.

i. Françoise d’Eaubonne, Le féminisme ou la Mort, (Paris: P. Horay, 1974).

ii. Karen J. Warren, “The Power and the Promise of Ecological Feminism”. Environmental Ethics 12, no. 2, (1990): 125-146.

iii. Val Plumwood, “Ecofeminism: An Overview and Discussion of Positions and Arguments.” Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 64, no.1, (1986): 120-138.

iv. https://unfccc.int/gender

v. https://www.shechangesclimate.org/cop28

vi. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/dec/27/we-have-a-responsibility-the-older-women-suing-switzerland-to-demand-climate-action?CMP=Share_AndroidApp_Other